David smiles at me and the world seems lighter. If that smile were in a toothpaste advert, I would buy that toothpaste. Because David is one of those people you like instantly. Goodness shines out of him, a kind of transcendent and spiritual assuredness of the world and his purpose in it.

That rarity – a happy artist. – David is not tortured or melancholic when it comes to creating his work. He is neither cynical, nor ironic, as so many 21st century artists are when dealing with the tragi-comedy that is the current world. Because he believes that what you do is an emanation of who you are. Your life is defined by your approach to it. For a generation constantly in search of “the right thing” – the right job, the right partner, the right handbag – we seem to see happiness as something external to us, a set of circumstances we achieve. In contrast, David says we need only look to ourselves in order to find that which we seek.

This is by no means easy; I imagine many people would rather bemoan the problems of the outer world than address the ones they hold within.

Spending a day with him, first at his family homestead in Sunnydale and then at his studio, made me realize how easy it is to be happy for people in our position: people that live from their passion and who don’t end up under a bridge when they are broke.

Suddenly, I wonder: How is it that I have had so many unhappy/grumpy/discontented moments in my life? When I look at David, it seems so easy to be happy. I would even love to be irritated by his smile and his happy mood, so I could find new reasons to say that pure happiness is not for me. But David is not the kind of irritating-smile person (I am sure you know what I am talking about). Rather, he generates thoughts like: “Share your wisdom with me, so I too can be the sun – not the black hole – in my own universe” (because the chanting in yoga this morning didn’t work!)

So, after a tour de la propriété at his peaceful old house surrounded by its garden of Eden, I am almost jealous of David. Growing up in such a nice, solid and pure environment may have been the reason why he has such a rich inner garden now.

But not only. Anyone can do anything with his/her past. Some pasts are harder to digest; others seem easier. But I am not sure a beautiful house in the valley is sufficient to make you into a David. Actually, I think you have to overcome many things to be a David because no one has an instruction manual for “undoing colonial oppression” and it would seem very attractive to see this heritage as an embarrassing burden from the past (as I believe I would have done, and so tried to disassociate myself from it).

But not only. Anyone can do anything with his/her past. Some pasts are harder to digest; others seem easier. But I am not sure a beautiful house in the valley is sufficient to make you into a David. Actually, I think you have to overcome many things to be a David because no one has an instruction manual for “undoing colonial oppression” and it would seem very attractive to see this heritage as an embarrassing burden from the past (as I believe I would have done, and so tried to disassociate myself from it).

Yet, there is a big difference between guilt and gratitude. When I ask him if he feels guilty about the fact that centuries ago, slaves built his house, he says: “No, but I feel grateful, because I know how hard it is to work on the land and carry stones.”

What follows is that there are always two basic ways of absorbing a situation: positively or negatively. And, with your choice, your emotions will oscillate in positive shades or negative.

For sure, David has had darker episodes. He is not blissfully ignorant and unquestioning. But, instead of being eroded by guilt, he chooses to create: to break down and rebuild. His art is part of a process of self-interrogation and acceptance.

In the past few years, David has had three exhibitions in which he drew on his own family history to explore the faux pas of white masculinity. As he says, being a young white male in South Africa today comes with a heavy cultural inheritance. In both society and the media, the white male is often – and not unjustly – characterised as the oppressor, the supremacist. While history holds much evidence for these labels, if one happens to be a young white man in South Africa, it is a dark cloud that can hang over one’s head. So David began a quest to “make peace with being a man.”

Detail: Man (2011). Reverse acetone print of Scope Magazine centerfold on fabriano.

David’s graduate exhibition, Vaderland (Fatherland), dealt with the enormous silence he felt hanging over his father’s generation – a group of men, or ghosts, involved in a conflict that is rarely spoken about: The Border War. These soldiers were our dads. If we had been born twenty years earlier they could have been our friends, boyfriends, brothers…

Recce I (2011). Ink on incised Facebook photograph.

Some of these men went willingly, others resisted (the End Conscription Campaign) and many just did what they were told. Inundated with propaganda of “Die swart gevaar”, they fought and died for a cause that was soon after seen as invalid and worse, wrong. The country and system they were defending ceased to exist. Yet the trauma and atrocities experienced, on both sides, as will always be when it comes to people fighting and dying in violence, remained.

Panga (Blackface) (2010). Gouache and Indian Ink on Found Object

Sour Figs (2011). Ink and Gouache on Apartheid-era flower illustration.

Patrol II (2011). Ink on incised Facebook photograph.

This burden has been borne in relative silence, and David’s work explores the experience of an unnamed space: Man on the edge of Nowhere. Being a man in the SADF was constructed as the epitome of masculine prowess, and you fought with your brothers because, my god if you didn’t, you were nothing more than a “fokken moffie.” It’s these kinds of words and ideas that David plays with in his work. He presents a direct criticism of hegemony and white patriarchy, by juxtaposing symbols of the South African army with images torn from natural history collections. Drawings of soldiers holding guns are half-covered with the delicate petals of an Erica flower or the body of a bird. There is a sense of nostalgia in David’s material – faded photographs, yellowing paper and the pages of antique books give the work a wistful aesthetic. The work is darkened, however, with Kentridge-esque elements: obscene words scrawled in black ink and faces scratched out of the photographs.

Scarlet-throated Sunbird (2011). Ink and Gouache on Apartheid-era bird illustration.

Bokkie (2011). Ink on incised Facebook photograph.

His work reflects the way in which the image of “a man” was heavily laced with violence, standing as a reflection of the political-hierarchical atmosphere of the time.

*

1969 was the title of David’s second exhibition and marks the year in which his grandfather led a rescue mission to one of the world’s most remotely inhabited places, Gough Island. Captain G. N. Brits, commander of the SAS van der Stel, led his men through the violent seas and blistering winds of the Atlantic, to reach the island, where two meteorologists were stranded in a storm.

At the height of the Cold War and in an era of state-controlled media, the Rescue to Gough Island demonstrated South Africa’s naval capabilities and became a symbol of national strength. The way the media portrayed this event, and David’s exploration of this, emphasize the symbolic power of white masculinity in history’s collective imagination.

Maj Gen P. M. Retief (Clasp). 2013. Hand drawn dot-matrix image. Ink on Fabriano Rosaspina.

Double Portrait: Capt G.N. Brits (Oupa) and Ian Flemming (Detail). 2013. Hand drawn dot-matrix image. Ink on Fabriano Rosaspina.

It is interesting to me, then, that David followed the wave-break of his forefathers: in 2013, having never sailed before, he boarded a small yacht with two other crew members and sailed across the Atlantic. This journey of 43 days and 6000 nautical miles was, in David’s eyes, “a rite of passage.” Virtually alone, surrounded by endless ocean, he was forced into a space of reflection.

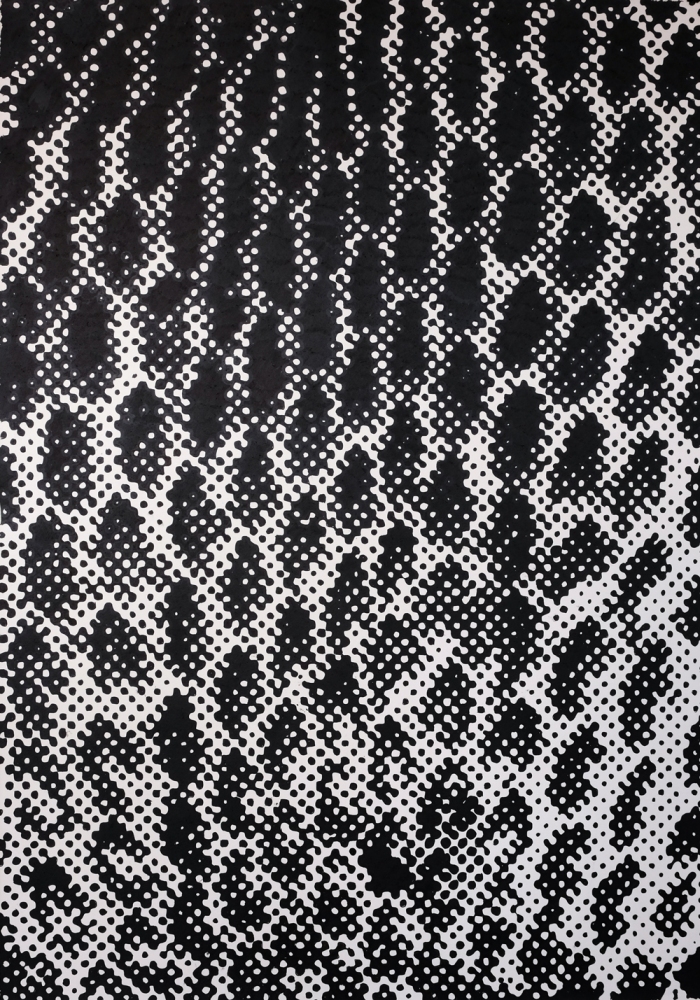

He tells me this, in his studio, as he carefully shades in thousands of tiny black and white dots on a large sheet of paper. Up close the subject seems abstract, but with distance begins to take on form. This process – dot matrix drawing – is one of his favored techniques and involves hours of re-rendering the pixel-like dots that characterized the printing style of the old photographs David has from his family archives.

He tells me this, in his studio, as he carefully shades in thousands of tiny black and white dots on a large sheet of paper. Up close the subject seems abstract, but with distance begins to take on form. This process – dot matrix drawing – is one of his favored techniques and involves hours of re-rendering the pixel-like dots that characterized the printing style of the old photographs David has from his family archives.

These latest ones are from his most recent exhibition, Snake Man, which celebrates the life of David’s other grandfather, John Wood. Wood was South Africa’s most eminent herpetologist (snake expert) and dedicated his life to studying those strange, symbolic and compelling creatures that hold such a prominent place in our collective mythologies.

These latest ones are from his most recent exhibition, Snake Man, which celebrates the life of David’s other grandfather, John Wood. Wood was South Africa’s most eminent herpetologist (snake expert) and dedicated his life to studying those strange, symbolic and compelling creatures that hold such a prominent place in our collective mythologies.

Over a period of sixty years he caught thousands of snakes, spiders, scorpions, lizards and frogs for both medical research and the development of snake and spider antivenins. He also had a traveling Snake Show, which showcased his various serpentine specimens and included uniquely intimate video footage that Wood captured of them (before the introduction of television in South Africa).

His passion for snakes was infectious to David, who spent hours looking at the photographs, films, newspaper cuttings, letters, poems, and priceless books that his grandfather left for him. The various artworks in this exhibition – series of linocuts, dot-matrix drawings and lithographs – take their inspiration from this archive.

Skin Abstract I – Gaboon Viper. 2015. Indian Ink on Fabriano Rosaspina.

Snakes and Ladders. 2015. Indian Ink on Fabriano Rosaspina.

The Handler IX. 2015. Indian Ink on Fabriano Rosaspina.

Skin Abstract II – Cape Cobra. 2015. Indian Ink on Fabriano Rosaspina

The Handler I. 2015. Indian Ink on Fabriano Rosaspina.

He took inspiration from a variety of sources: ME Escher’s mystical pattern-like worlds, as well as that of the old masters and pre Columbian art (art from central and South America before the arrival of Columbus).

Snake Abstract 3.1. Linocut on Zerkall Litho Paper.

Snake Abstract 3.1. Linocut on Zerkall Litho Paper.

Snake Abstract 3.4. Linocut on Zerkall Litho Paper.

In the process of making these works, David felt himself to be more of a channel for creative energy than the owner of it. He experienced long, almost meditative periods of intense productivity and inspiration.

Unlike his previous exhibitions, Snake Man, highlights something of the sacred and the spiritual; a different form of masculinity to that which is inherently systemic and patriarchal. We see the pursuits of a man with a fascination and admiration for the natural world and a desire to share in knowledge and beauty.

David’s own attitude to the world is much like his work: nostalgic and romantic, but not romanticized. He says he has always had a fascination with and magnetism towards the historical, the ancient and the sacred. Indeed, David is something of a contemporary pilgrim. He spent thirty four days doing the camino de Santiago, crossed the Atlantic, and has returned several times to an ashram in the North of India. Similarly, his body of work reflects a personal journey towards embracing his family heritage and identity.

Thus, in a life peppered with pilgrimages, whether artistic, personal or physical, David seems to have found the secret, the holy grail promised by Hollywood and advertising, that which we all seem to seek in the endless cycle of life; happiness.